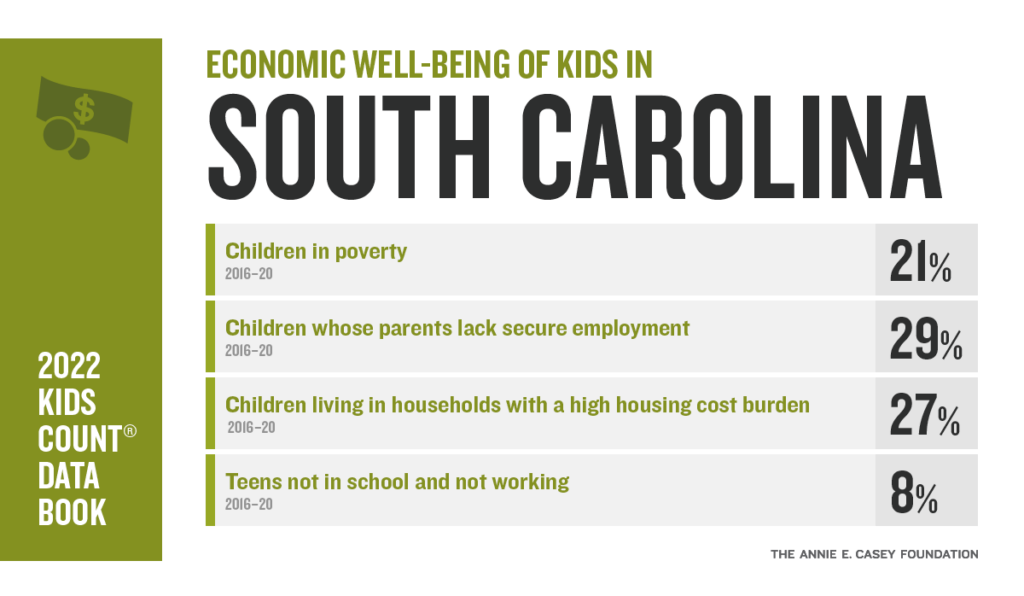

South Carolina ranks 37 in child economic well-being, according to the 2022 KIDS COUNT® Data Book. The 50-state report of recent household data developed by the Annie E. Casey Foundation analyzes how children and families are faring.

The annual Data Book uses indicators from four key domains — economic well-being, education, health, and family and community — to produce an overall child well-being ranking for each state. South Carolina persistently sits near the lower fourth of states, with this year’s rank at 39.

In a four-part series, Children’s Trust of South Carolina is exploring the reasons behind each domain ranking.

To better understand how economic well-being impacts children in the state, we interviewed experts in the field, including Sue Berkowitz, director of the South Carolina Appleseed Legal Justice Center, a statewide nonprofit legal advocacy group in Columbia; Tiffany Santagati, vice president of operations at the Greenville Housing Fund, a nonprofit that works to champion affordable housing in Greenville; and Lila Anna Sauls, president and CEO of Homeless No More, a shelter and social services agency in Columbia.

What are some of the causes for South Carolina’s low ranking in economic well-being?

Sue Berkowitz from Appleseed: Historically, South Carolina has not put resources into programs that will help improve the lives of low-income people. We have not been willing to invest in human infrastructure, education, affordable housing, transportation services, healthcare assistance and living wages.

Sue Berkowitz from Appleseed: Historically, South Carolina has not put resources into programs that will help improve the lives of low-income people. We have not been willing to invest in human infrastructure, education, affordable housing, transportation services, healthcare assistance and living wages.

All of this has had a long-term adverse impact on the people of our state. This coupled with our history of racism and lack of inclusiveness has all added to our poor economy and inability to move past many of these adverse factors. When we have had financial opportunities to make these investments, our policy makers have ignored them and opted for policies that have ignored economic growth and providing to those in need.

Tiffany Santagati from Greenville Housing Fund: South Carolina suffers from a lack of economic mobility opportunities throughout the entire state. In Greenville County, there are numerous childcare deserts, low opportunities for economic mobility, the expense of healthcare and the impact having little to no healthcare has on families, an inequitable educational system and very few social safety nets. So when people fall on hard times, they have very few places to turn for help.

Tiffany Santagati from Greenville Housing Fund: South Carolina suffers from a lack of economic mobility opportunities throughout the entire state. In Greenville County, there are numerous childcare deserts, low opportunities for economic mobility, the expense of healthcare and the impact having little to no healthcare has on families, an inequitable educational system and very few social safety nets. So when people fall on hard times, they have very few places to turn for help.

Sadly, South Carolina ranks 43rd in education, and this number looks even worst when you look at numbers for Black and Brown children. In Greenville, Black and Brown children make up almost 50 percent of the Greenville County schools population; however, most of these children are in

poverty—81 percent of Black children and 76 percent of Hispanic children. With Greenville having a low opportunity for economic

mobility, we can see how the cycle of poverty and lack of economic mobility continues to perpetuate itself.

Dr. Lila Anna Sauls from Homeless No More: The majority of the families we serve simply don’t earn a sustainable wage to support housing, childcare and basic needs. We also don’t support working parents with paid parental leave—for birth or during sickness—and often find that parents will lose employment when a child has an illness that lasts more than one or two days.

Much of the KIDS COUNT data was collected before the pandemic. How have you seen the pandemic influence the high housing cost burden and lack of secure employment?

SB from Appleseed: It was bad before the pandemic, but we see people struggling more now than ever. Evictions are problematic, and as a right to work state, we see people have few if any protections from employer abuse, low wages and lack of benefits. The pandemic has only made it worse.

TS from Greenville Housing Fund: Rent has jumped from 14 to 19 percent since the pandemic due to out-of-state investors which have caused displacement. This impacts the workforce. Anything that impacts the workforce impacts child well-being.

We have seen families lose disposable income due to rent increases, and we have seen people move to different places in the county or even outside of the county, uprooting their children to avoid a squeeze on rent.

LAS from Homeless No More: We did not advocate for the continued extension of the rental moratorium towards the end of 2021, as it became clear many renters did not realize they would be responsible for the full amount of rent owed and many landlords were choosing to end leases versus evicting.

Assistance was slow in reaching families and came too late for many. We’re in an unusual situation in that we provide shelter for families who were displaced, but we also are in a landlord relationship with other families at Live Oak Place, an affordable housing option for working families who qualify. The common denominator seems to be a lack of budgeting skills. Even with assistance, many families found themselves unable to cover rent.

We continue to push for ARPA funds to be used to support the development of affordable housing with services, so families do not find themselves needing another moratorium again.

The KIDS COUNT Data Book also shows South Carolina has experienced one of the sharpest increases in children and teens reporting depression and anxiety since 2016. How does economic well-being affect the ongoing mental health crisis among youth?

SB from Appleseed: I can only imagine how difficult it is to be a youth right now, watching families struggle, seeing violence against each other, and for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) children, not knowing if you will be judged or hurt by the police. Family instability due to economic fluctuation is only going to make it worse.

TS from Greenville Housing Fund: Children are not immune to community stressors. When their parents stress, they feed off of that stress. As rent increases, this creates more financial stressors for families. If your parents are afraid or concerned, this leads to anxiety for both the parent and the child.

In addition, some children move several times within their elementary years due to housing insecurity, which adds additional stress to their lives. In fact, in some areas of Greenville, two out of five students move in a three-year period which can impact their sense of safety, security and overall well-being. Sadly, this statistic holds true for their teachers, creating less consistency in schools and in the children’s lives.

LAS from Homeless No More: I have five children. They sense when I’m stressed. They know when there are issues in our household. The children I serve are the same.

Between e-learning, fear of sickness (of their own and their family), the lack of socialization, and a fear of where they will spend the next night, how can you expect a child to not have depression and anxiety?

We have increased our children’s team at Homeless No More and are increasingly watchful over our youngest clients as we make mental health referrals. And we continue to work towards helping their parents achieve enough financial stability to give them what every child deserves—a home.

How is your organization addressing this issue of economic instability? And what can policymakers, state leaders and the general public do to improve the economic well-being of children and families?

SB from Appleseed: We have worked for two decades to help develop sound consumer protections for homeowners through writing and working for the passage of anti-predatory home lending laws.

In addition, we are working to limit the number of evictions in our state. We worked with U.S. Rep. James Clyburn’s office to develop funding streams to help get legal representation for people in eviction matters.

We have been participating with the City of Columbia’s affordable housing task force. We have also been working with national partners to work for more programming and programs through the federal government.

TS from Greenville Housing Fund: Economic mobility is tied to your zip code, so as we look at the social capital of low-wealth communities, we see they start out behind. Greenville Housing Fund’s goal is to focus on disbursing income levels throughout zip codes to better balance social capital while providing a safe, stable and healthy place to live. We believe everyone deserves affordable safe housing.

Community members can be an advocate for affordable housing projects. Speak to your council members about the need for safe affordable housing and how it lifts the entire community.

Legislatures can create policies to support all types of housing and housing typologies, affordable housing incentives and reduced barriers to affordable housing. It is also important for them to understand the overall impact of affordable housing on the city. We cannot have a vibrant downtown without affordable housing as a focus.

LAS from Homeless No More: Our organization is a system of programs for at-risk and homeless families. Through our shelter programming, we offer emergency, 30-day services and two-year transitional housing.

The key to both is our wrap-around services for all members of the family, including case management, mental health referrals, budgeting and other life skill classes for the adults, as well as a full spectrum of services for the children. We also provide after-school and camp programming, and we assist families in securing childcare for younger children.

We began developing affordable housing in 2015 and will have 200 units across the Midlands within the next two years since those graduating from our programs had no place to live that they could afford. And most recently we have started a pilot home ownership program to build generational wealth. Access to quality childcare and after-school programming is key for the children, just as increasing employability and income is key for the adults we serve.

We continue to advocate for programs that support the funding and development of affordable housing throughout our state. This topic has not been on any agenda at the state level and must be addressed as we have children living in both rural and urban areas in homes with no electricity, no running water, or in homes with three or four other families.